Let's do a quick exercise...

Pretend I am the chairman of the board for your firm. In our annual planning meeting, I tell you that we need to raise prices by 4x. What's your initial reaction? Grab a pen and paper, and write it down.

This is the exact exercise I do with founders at the beginning of my pricing workshop. Here are some of the most common responses:

"No"

"I can't"

"I'll lose all my clients"

"I'll need to change my entire offering and have 4x the value"

The assumption they all operate under is that price is a dependent variable and it's mostly out of their control. They operate from a place of fear and impostor syndrome. This week's article is all about getting you to realize that it doesn't have to be that way.

Don't let impostor syndrome set your prices

When I first ask founders of boutique firms, what their core value proposition is, many respond with something like "we offer Big 4 value without the Big 4 price". They say this with a sense of pride. Yet in the same conversation they will often say things like "we can't just throw a bunch of bodies at a problem" or "we don't have the capacity and resources to put together the propiretary research and frameworks like the Big 4" or "we can't attract the type of talent that they do because we can't pay as much". At face value they are talking about their price-to-value offering with pride, but on the inside, they are scared that they can't justify a higher price which is why they are actually charging less.

This is impostor syndrome at it's worst. Have you ever asked yourself "who am I to charge this much?" or "how can I charge this much when this other person charges this much?" When you compare yourself to others, you are actually making assumptions, often unfounded and unsupported, about the value they bring and the risk profile of the people they sell to. And we all know what it means to ass-u-me, right? This is why for boutique firms, I recommend that you don't do any competitor pricing analysis up front. Anchoring your pricing to competitors creates a fake ceiling, because it positions price as a dependent variable - making it dependent on what your competitors are doing.

Yes, the rules of supply and demand still apply, but as a boutique firm, your target market share is likely so small, that you can find a part of the market that will pay you what you want. And at the end of the day, those market dynamics will lead you to the right price eventually. Yes, you may need to adjust your price and pricing depending on what your competitors are doing, but that's a strategic decision based on your positioning, so focus on that first. And positioning is all about how you want your ideal clients to see you. Replace “what do others charge?” with “what outcomes matter, how will we measure them, and what would the lowest-risk choice for this buyer?”

Don't conflate price and pricing

I often hear "price" and "pricing" being used interchangeably, and that's another factor holding many firms back from being as successful as they could be. Price is the visible sticker price that someone pays for your service. It's the total economic value being captured. Pricing is the activity of selecting that price, and everything else that guides how and when the cash moves. It's the structure, terms, sequencing, anchors, etc.

There's a reason why consumer financing is such a big deal. I recently purchased a $13,000 Sleep Number bed. That thing moves, heats, cools, tracks sleep, etc. I put a high value on a good night sleep, so the value makes sense for me, but spending that much on a bed is crazy. But I didn't pay it up front. I am paying roughly $325/mo at 0% interest. That's the difference between price and pricing, and the same is true for consulting and other professional services.

What if you charged more, but spread it out over installment payments? What if you charged more, but offered Net-30? What if you charged more, but split it out over phased scope with concrete milestones that de-risk a particular decision? What if you gave yourself more upside by having a base fee with a performance based incentive? What you charged more by offering a fixed fee model that provides cost predictability to the client, instead of an hourly time+materials model? What if you have a tiered pricing structure, where you vary how quickly milestones are reached?

I think you see the point. And you can mix and match all of the above. You can get creative with your pricing structure, to support the price you want. But make sure you first understand why you are messing with price and pricing in the first place.

Are you solving the right problem?

Do you have a profit problem, or a cash flow problem? These of course aren't the only two that exist, but they are two of the most common ones that firms have. If your problem is profit, then charging more for the same amount of work can be the solution. But if your problem is cash flow, then charging more will help eventually, because you will end up with more cash in the bank over time, but it's a longer-term impact and more indirect. Changing your pricing terms however, where you get paid for everything up front, will do wonders for that cash flow situation.

The reality is of course not that black and white, because changing your price will impact which clients stay and they type of clients that come in the future. If enough clients leave, but you charge more of the ones who stay, you may be left with the same cash flow problem if you have full-time staff, which means you will possible need to downsize, at least temporarily. The pricing structure and terms you update, will impact when cash comes in, and if your new pricing strucutre delays cash enough, you may be put in a position where you will feel that you need to discount to win more deals to get more revenue through the door. The main point still stands though - pricing is an independent variable that you control. You just need to understand how the market will respond to it.

Price is an independent marker of value and confidence

The entire luxury industry is predicated on this concept. You can buy a Timex or you can buy a Rolex. Same function; very different price. The same is true of consulting services. Your price broadcasts status, standards, and how seriously to take you. Let's take my favorite "we deliver Big 4 value at a fraction of the Big 4 price" firm. Forget the fact that they have positioned themselves incorrectly for a moment. They have also potentially priced themselves out of certain conversations, not because they are too expensive, but because they are too cheap.

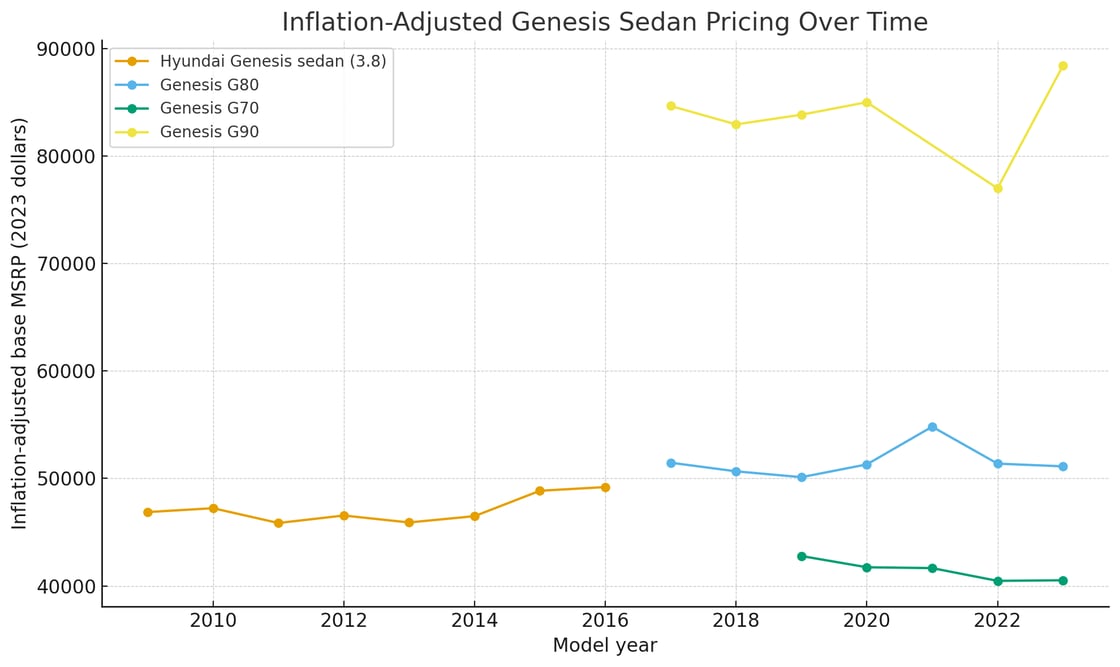

If you price too low, your prospective clients will wonder "what are they not including, that I would get with McKinsey?" or "I've paid way more than this in the past, how good are they at actually delivering these results?" Your buyers often have an expectation of what things should cost, and if you deviate from that too much, it raises a flag in their minds. Here is another consumer pricing example - Hyundai Genesis cars.

You can see that over the years, prices have risen on an inflation adjusted basis, and they even added in an even more upscale model. Why? Because you can't compete in the luxury car segment without the luxury car price tag. Buyers won't take it seriously. When we buy cheap stuff and it breaks, we say "well I guess you get what you pay for". And there are certain things we are willing to pay more for, because we don't want to risk them breaking too soon.

The same is true with professional services, especially from the risk perspective. Depending on who your buyer is, they are first looking at the decision from a personal risk perspective - "will I get fired if this goes wrong?" Your price should give them confidence that you know what you are doing and that you've done this before. Your pricing structure should take away some of the pain of buying and de-risk the decision even further.

Who is carying the risk?

Warren buffet said that "price is what you pay; value is what you get. Risk is the flip side of the value coin, so I would also add that risk is what you choose to carry. Risk is the burden of uncertainty, and there is uncertainty on both sides of a transaction. On client's side, there is uncertainty in the outcome of your service. On your side, there is uncertainty on the profitability of delivering the service. And depending on your terms and pricing structure, the two are interrelated because if you invest a bunch of time up front, and the client can cancel early if they don't feel you are delivering value, you may be left holding the bag.

When crafting your pricing strategy, it's important to remember that both value and risk are in the eye of the beholder, and your clients are always looking for assymetrical risk/reward scenarios, but they are much more sensitive to risk - the uncertainty of losing something. The work of Daniel Kahneman has shown that.

Complicating this even more, is that different people on a buying committee, within the same organization, will view value and risk differently, and much of this is due to whether it's their money, or someone else's. A founder of a company might be wondering "how will this help me increase personal cash flow over the next 5 years and how much of my personal cash am I risking here?" An investor in that same company might be wondering "how will this help me increase the value of this company in 3 years and what's the worst case scenario if it doesn't work?" A VP at that same company might be wondering "how will this help me get promoted and what's my risk of being fired if it doesn't work?" The conversations you will need to have about price and pricing with each of these stake holders will be different.

So from your perspective, you need to decide how much value you want to offer versus how much risk you want to carry. Want upside? You’ll take more risk. Want stability? You’ll trade some upside. Your pricing model is downstream of the promises you are willing to make. But realize that you don't have to make this an all-or-nothing choice. You can choose to play with several pricing models to manage your overall risk across your client portfolio.

If you feel that you are carrying too much risk with performance based incentives, take 20% of your client base, and switch them to fixed fee retainers. Or if you feel like you would like to play with more upside, go the other way, make your next few pitches base + performance incentive. Feel like you aren't closing enough deals, and willing to take on more risk? Consider longer net terms and/or monthly payments with a higher all-in investment, instead of upfront payment. Feel like cash is getting tight? Consider slightly decreasing all-in investment, but taking money upfront on the next few deals.

Pricing pitfalls to avoid

Remember, price and pricing are independent variables. Feel free to play around with them, but be sure to avoid some of these common pitfalls:

- Good, Better, Best pricing. The problem here is that good usually turns into "good enough". And nobody wants "good enough". One of the first lessons I learned in design school back in the day was to never show a client a concept that I didn't like. The same is true of service structures. If you know that a service is only "good enough" then it will show both in how you do the work, and the results you are able to drive. Which in-turn will hurt your ability to retain that client and get referrals from them. Each tier should be maximal value for that given price. This is where I like the time-to-value abstraction. You're shooting for the same outcome, but at a different pace.

- Perceived value mismatch across service offerings. Yes, it's a good idea to have an entry-level offer where new clients can pilot working with you, but if you price that too low compared to the rest of your offering, the jump will be hard for them to make, and it will also make the perceived value of that initial offer very low, making it not very attractive.

- Having too many pricing options. Your clients aren't buying complexity - they have enough of that already. They are buying clarity and confidence. If you present them with too many pricing options, it can decrease their confidence in you and the likelihood of getting the promised results. It also plays negatively into the decision fatigue they liekly already have. And on your side, having too many options to work with, where every single proposal is completely custom from a pricing structure perspective is a nightmare, from an operations perspective.

- Anchoring to competitors. We've already talked about this, but it's worth repeating. Anchoring creates a fake ceiling, and forces you into building someone else's service for someone else's clients.

Start with price

Rather than asking "how can I increase prices by 4x?" ask "if I increase prices by 4x, what needs to be true?" Thank you Peter Giordano III for sharing this one with me. I've done this type of "what needs to be true" exercise for many other things, but never for pricing. Don't start with a limiting belief. Start from a place of abundance.

Based on your desired price, identify your ICP, map your risk (e.g. delivery control, administrative overhead, performance upside, etc.), choose your model (inputs vs. outputs vs. outcomes), design the terms (e.g. payment cadence, milestones, net terms, etc.), stage the journey (e.g. entry project, tiered of phased path, etc.)